Forgotten today, Fenwick Umpleby Helped Launch Two State Universities

By Bernie Zelitch

for the Lowell Historical Society Fall 2024 Newsletter

DARLING OF THE PRESS– Although practically unknown today, this article from the Sun Nov. 27, 1900, is one of over 100 interviews and society page notices Fenwick Umpleby received in his 13-year career at Lowell Textile School. Reporters noted the design teacher’s wit , ability to motivate students, and explain technical concepts simply. Letters he wrote to his superiors suggest a strained relationship that may explain a lateral career move to Lowell’s competitor in Fall River. (Fig. 1)

Today, you won’t find a Fenwick Umpleby building, memorial, or even coffee shop at the UMass Lowell or UMass Dartmouth campuses. Yet these schools owe much to his early leadership as a teacher of high standards, principal, and promoter of arts and sciences degrees.

Born in 1852 in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, England, Umpleby was the second of six children of Thomas and Tamar Fenwick Umbleby. With a name seemingly out of a Dickens novel and a near-incomprehensible regional accent, he was a bigger than life voice and face of Lowell Textile School from 1897–1910. He then oversaw growth of Bradford Durfee Textile School, Fall River, until his death in 1913. These technical and design schools evolved to UMass Lowell and UMass Dartmouth.

Umpleby interviewed well and organized public open houses, exhibits, and lectures. He wrote important technical books and edited the widely circulated Textile Journal. His popular art and design department featured evening classes, and is surely one reason the Lowell school grew exponentially from seven students to several hundred in a few years. With a spreading reputation, the school soon drew students from the deep south and as far away as Japan. He had a similar effect in the three years he was principal at Fall River.

“Mr. Umpleby was one of the most popular members of the faculty at the Textile school,” a Lowell Sun reporter wrote on the teacher’s departure for Fall River in 1910, “and the students of his classes will regret his leaving the local school.

“He took a great deal of interest in the students and many of the graduates of the school who are now holding responsible positions are in no small measure indebted to Prof. Umbleby, whose manner of explaining the work and encouraging the students to study hard resulted in the turning out of graduates who were competent to accept big positions and fill them in a capable manner.”

Opening the school with just seven students, the Textile School leaders drew heavily from textile managers and eduactors from the United Kingdom. President A.G. Cumnock (for whom Cumnock Hall is named) was from Scotland and he brought over Christopher P. Brooks from the Manchester mills as first principal. He in turn quickly recruited Umpleby in early 1897. He would have known him as a textile star in Manchester, but by then he was in nearby Gilbertville, MA, working as head designer of H. Gilbert Manufacturing. It was the latest entry to an impressive resumé: numerous European technical and design awards and increasingly responsible positions in Canadian and American mills.

RECRUITING women to the early Textile School was a mandate from the state legislature. But it may also have become a strategy to fill seats. This 1898 free lecture “of interest to the ladies” was likely a recruiting tool for Umpleby’s arts and design evening school, expanding the technical school’s base with a career path that seemed realistic for women at the time. In its early years, in addition to enrolling women students, the school employed two women teaching assistants. (Fig. 2).

In 1896, with just a capitalization of $50,000 from taxpayers, the early leaders rented the upper two floors of what is now Middlesex Academy Charter School on Middle Street. They gambled to pay competitive salaries from the start. Umpleby, the school’s fourth employee, earned $2,400 a year by 1902, just $100 less than the school’s principal. (That is nearly $90,000 in today’s dollars. The next highest salary, $2,000, was chemistry and dyeing teacher Louis A. Olney, whose name is on the Olney Science Center.)

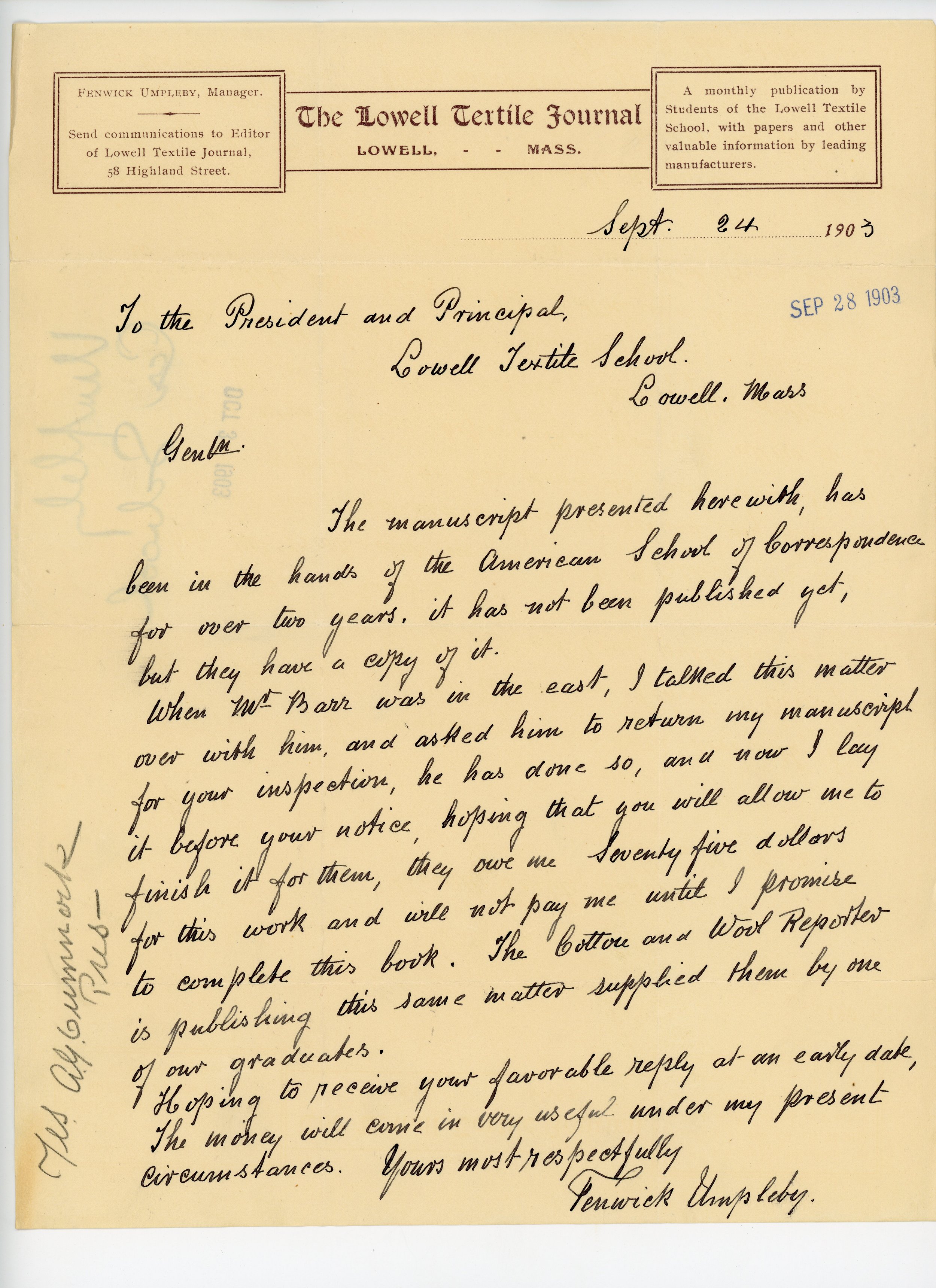

WORKPLACE GRIEVANCE— According to Umpleby’s 1903 complaint to Principal William Crosby and President G.A. Cumnock, Umpleby suffered financially due to their two-year failure to approve his $75 book advance. This pleading was apparently unheeded as Textile Design came out in 1909, a full six years later. This and other sources preserved at CLH expose a poor working relationship. See transcription. (Fig. 3.) transcription

Source: Umpleby, Fenwick. Letter to President and Principal of Lowell Textile School, 24 September 1903, Box 2, Folder 8 - Lowell Textile Journal, University Archives, Lowell Texile School- Miscellaneous. Center for Lowell History, University of Massachusetts Lowell.

The founders considered European textile training as a model, but were more inspired by the rigorous engineering training offered at nearby Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

There was an educational innovation which Umpleby knew from personal experience: community outreach through evening school. A factory manager in England by the time he was 18, he was able to advance his education through evening classes at Yorkshire College. School leadership might also have noticed the popular evening arts school operated by the city on Dutton Street and Broadway. Umpleby’s design evening design class would have offered the same after-work convenience with the benefit of a career advancing certificate. This would have lent a community college aspect to the budding institution.

Umpleby’s design class was required all three years for day students earning a diploma. The department offered regular public exhibitions of projects, becoming a public portal into the school. Umpleby’s roles as teacher, editor, and writer meant he was working day and night. For a time, he even commuted to teach a class at the Boston Normal Arts School.

DESIGNING MEN— In 1901, Fenwick Umpleby posed in a wicker chair with members of his fabric design class. In time, the class attracted women who sometimes became art teachers. The photo was taken by John or Annie Powell who also took machinery photos for Umpleby’s Textile Journal. They used that chair and backdrop for their South Lowell studio as well as other portraits at the early Textile School on Middle Street. Society page notices show that the Powells and Umpleby families, all from the same British city, were close friends. (Fig. 4)

A study of Umpleby’s articles, books and surviving notebooks, some at UMass Lowell’s Center for Lowell History (CLH), shows a brilliant mind able to understand the mathematical, chemical, and design intricacies that drove textile mills in the early 1900s. A man of curiosity, talent, and tireless energy, he was also an accomplished musician and expert on the technology of photography.

And, we have several first-hand accounts of students on the town making late calls to Umpleby’s house or office. Here are two from the Lowell Textile Journal (1900-1902), the second being on election night:

From Belvidere the line of march was taken to Centralville where several calls were made, the most important being upon Professor Umpleby (83 Third St.), who appeared at the window robed in white, and informed the merry-makers that he "would be down in a minute." Upon his reappearance, in different garb, the Professor made a short address containing good advice, and finished by advising the boys to retire.

They met at the school, and with canes carried at rest, and school flags flaunting in the air, escorted Professor Umpleby, who had just finished an arduous night at the school, as a guest of honor through the vast throng in Merrimack square, to a place where he could get the election returns. The square rang again and again with the familiar Textile yell and after cheering Professor Umpleby, they proceeded to the Savoy Theatre…

The news of his leaving came under large headlines in the Lowell Sun of Aug. 13, 1910:

Mr. Umpleby was one of the most popular members of the faculty at the Textile school, and the students of his classes will regret his leaving the local school. He took a great deal of interest in the students and many of the graduates of the school who are now holding responsible positions are in no small measure indebted to Prof. Umbleby, whose manner of explaining the work and encouraging the students to study hard resulted in the turning out of graduates who were competent to accept big positions and fill them in a capable manner. (Lowell Sun, Aug. 13, 1910)

He left for more responsibility at the same pay; there may be an explanation. He wrote two letters to management which suggest an untenable working environment. In addition to Fig. 3, which accuses them of holding up a book advance for two years, a letter from August 1902, suggests they denied him reasonable authority as the Journal editor. “Dear Sir,” he wrote to the principal, “According to contract I require your sanction and good will in order that the ‘Lowell Textile Journal’ may continue as usual.”

No responses to these letters survive, but it’s a good guess that a factor was professional resentment: from management’s point of view, he stole the limelight. “Prof. Umpleby Tells of His Trip Abroad,” is the headline of a Sun interview September 18, 1901. We learn “Prof. Crosby” was also on the tour of factories and textile schools abroad. This man, with no first name or quotes, was in fact more than a professor. William W. Crosby was the principal of the Textile School!

Who was Madame Josephine?

We don’t know her last name before she asssumed “Umpleby” on her marriage to Fenwick around the time of this ad, April 17, 1907 in the Lowell Courier Citizen. In the 1906 Lowell City Directory, there were 217 women in the “dressmakers” listing. That included six with first names of “Josephine” who were not this one as their last names persisted.

Umpleby’s family life holds mystery. He married Frances Marshall in 1847 and they had ten children. They raised another daughter born in 1874 who, on investigation, was actuarlly their grandchild born to their unmarried daughter.

In 1893, while a mill manager in Worcester County, Umpleby and a woman known only by her first name, Caroline, had a daughter out of wedlock, Nellian Phoebe. Known as “Phoebe”, she was adopted by the Umpleby family and received the same music lessons and boarding school as her half-siblings.

Frances died in 1903. Although there is no official record, by 1907, Umpleby married Josephine, also of unknown last name. She was born in this country of French Canadian parents and studied fashion and dressmaking in Paris. On sharing a home at 88 Mt. Vernon St., she ran display ads for her fancy dressmaking shop.

In Sept., 1911, Phoebe and Josephine were on site when Umpleby toured his Fall River school for President Howard Taft. That is Phoebe’s last mention in the public record. As for Josephine, almost a year later, while Umpleby was principal at Fall River, she operated a dressmaking shop in Lowell and had to file for bankruptcy. The next and final time Josephine appears in the public record is in 1923 as a widow working as a dressmaker at her home at 571 Westford St.

If Umpleby abandoned Josephine, this belied his reputation as a bon vivant full of grace and generosity. As a 29-year-old in England, he played piano to benefit victims of a fatal mill disaster, raising the equivalent of $3,000 in today’s dollars. A Sun reporter attended his 50th birthday party in 1902. “Professor Umpleby himself was the accompanist of the evening,” he said in an effusive 800-word report with a partial guest list, “and he also played several piano solos. His tact as a host and his witty remarks put everyone at their ease.”

Fenwick Umpleby is buried at Edson Cemetery in a plot with his first wife and a daughter, Frances Umpleby Stanley.

References, credits and further reading.

Example of West Yorkshire accent. Click on the West Riding selections. The Netflix series, Last Tango in Halifax, was filmed in West Yorkshire and shows the accent lingers into modern times.Willets, Gilson (1903) salary survey from Workers of the Nation, Gilson Willets, volume 2, P.F. Collier and Sons, New YorkUmpleby (1909) Textile Design, 1909, American School of Correspondence, LondonUmpleby, Fenwick (1910) Design Texts, Lawler Printing Co., LowellMerrill, Gilbert R. (undated), summary of early Lowell Textile School history by member Class of 1917 and teacher, CLH.Edson Cemetery recordsUMass Dartmouth Archives, Bradford Durfee Technical Institute newspaper clippingsCLH, Textile School collectionTranscription of Umpleby letters, Fig. 3Thanks to Huddersfield & District Family History Society for geneological research and newspaper clippings of Umpleby's early life in England.